The Scale of our Relations: Reflections on the Practice of Fish Scale Art

Erin Konsmo

Introduction

Fish scale art is a contemporary Indigenous art form that uses the scales from atikamek, known in English as lake whitefish, to create elaborate miniature florals. This material culture reflects the vibrant relationship that many Indigenous people have with fish and the waters. Fish scale art is primarily practised by Métis, Cree and Dene people with many artists within or connected to the Alberta region. I am mentored as a fish scale artist by Métis artist Jaime Morse from Lac La Biche, Alberta.

My current artistic practice includes time on the water and ice, the act of fishing, the processing of fish and the creation of both physical and digital fish scale art. Queerness propels us towards worlds where we relate to that which is around us in a multitude of styles. Not only in what is seen as conventional (i.e traditional fish scale art) but queerness allows us to create from our own articulation of how we see ourselves relating. I am propelled by a practice that honours the gifts of the fish, embodied queerness on the water, queer aesthetics, scale and orientation. My artworks reflect both the history of this artform and my own orientation towards this material culture. This orientation focuses our attention on not only the decorative beauty that comes from fish scales, but also the relationships that are built up through this material form. Relationships of transformation guide how we interact and live in a world with fish.

Fish/Scale Cones, 2020, Erin Konsmo

Fish/Scale

Fish/Scale is a play on words that speaks to the scales of fish used in this art form, in addition to the size (scale) of these vibrant gifts. Playing with the notion of scale is a way of re-centering fish relations, including their many gifts. Scale can help orient us towards relations less seen and to challenge the power dynamics of anthropocentric worlds. Using macro photography to capture the close-up qualities of an individual fish scale, those viewing this art form get a more intimate picture of the gifts from the fish. My artistic practice with photography and digital art allows for this art form to be presented in larger formats, such as murals and large prints. Transforming individual fish scales to life-size art increases the physical presence of fish scales, calling on the viewer to reconsider their role.

Indigenous relations to fish and other non-human kin have been greatly impacted by settler-colonialism of the land and water. ‘Scaling’ or resizing the gifts from the fish is about rescaling kinship,orienting towards our non-human kin and rescaling of power. Within my fish scale practice, scale is one ongoing strategy of ensuring fish are not overlooked.

Gifts from the Fish

The language used for describing our fish relatives is also an anti-colonial tool. Engaging NamekosipiiwAnishinaabeKwe Kaaren Dannenman’s (2019) phrasing “gifts from the fish” to recenter what is seen as waste or discardable as something to be cared for, I use the term “gifts” to refer to all parts of the fish including those often seen as something to throw in the trash.

This language comes from Indigenous teachers such as Jaime Morse and Treaty #3 Anishinaabe Land-based educator Kaaren Dannenman. When I took the Treaty #3 Trapping Course with Kaaren, she had us go through and list all the gifts from amisk (beaver)—a practice grounded in the ethics of honouring the whole life of the animal. This process of listing and considering the whole animal changed the pace and relation in which interactions with amisk would proceed. This caring language taught me to slow down, learn about the various parts of an animal or fish, a practice that extractive trapping, fishing and hunting practices often don’t make space for. Some of the gifts from amisk are returned and recirculated to the water or land, while others are encouraged to be utilized. This practice of slow consideration taught me about how honouring the animal or fish wasn’t so much about using all the parts of the animal as certain parts may be returned, but rather recognizing that there is purpose or intention to each part of any living being. While fishing in Treaty #6 with Cree Elder Lynn Jonasson, we gutted a fish after we had pulled the net and then left their guts out on the ice as an offering for the eagles in the area. It wasn’t only us who were benefiting from the gifts from the fish, but also the bird relatives who live around the lake. I understood this practice as an offering and a way of sharing with other relatives.

Many of the gifts from the fish are used in practices of Western Science though often are not thought of as gifts. Instead, Western science views gifts from the fish as necessities for material study. For example, to determine the age of a lake whitefish or to determine seasonal growth use “opercles, otoliths, pectoral spines, dorsal spines, scales and vertebrae” (Jackson, Quist & Larscheid, 2008, p.108). This is an example of how Western scientific research maintains relationships with lake whitefish versus Indigenous understandings of Land and reciprocity and kinship with atikamek. Having first encountered this practice through Michif scientist Max Liboiron, I capitalize Land and Water when referring to the connected relationships and spiritual practices engaged on the Land as a site of cultural significance, rather than lower-case land as a static geographical and physical entity (Styres and Zinga, 301). However, Western science and relationships do not exist in a strict binary. As a fish scale artist, I deepen my understanding of atikamek by reading research by Western scientists, alongside the work of fellow Alberta Métis and anticolonial scientist Liboiron. Their lab protocols follow an often-cited Indigenous value of wasting as little of the animal as possible and honouring all the gifts provided. As Liboiron asserts:

These food webs are not out there in the field, external to either laboratory or daily life. They are our food webs. Some lab members are from Nunatsiavut and NunatuKavut, some are daughters of fish harvesters, and most of us eat local fish (if we eat fish). The lab has a rule about samples; they must be eaten. We do not catch fish for science. We use fish caught for food, and we do science on the leftovers. (2021, 150)

The gifts from the whitefish are numerous, including fish scales, otoliths, vertebrae, fish skin, broth, meat, and the head. Each of these gifts have a purpose for their use, ranging from fish scale art, fish skin leather, numerous recipes, support for mental health, glue and rattles.

Anishinaabe scholar and artist Susan Blight speaks similarly of the sturgeon and the gifts that they offer:

Abundance is different from amassing or acquisition or even quantity. It is a way of living in the world that sets actions in the service of balance and a deep knowing that we live on land that continually grows and replenishes. The abundance was not due to a reckless and unrestrained drive to collect as much as possible but to an acknowledgment that sturgeon sustained Anishinaabe life, itself a practice of promoting more life (2020, 4)

Caring for all components of the fish is a queer form of care for the fish, in that it takes what otherwise might be seen as discardable and creates beauty. In a world where homophobia and transphobia are still present, queer care extends to our human and non-human family. When you come to understand the many different gifts from the fish, it’s hard to see them discarded so carelessly. As Michif anthropologist Zoe Todd generously reminds us, “fish are an integral part of Indigenous legal orders, and we can and should think through our responsibilities to one another by also considering the duties and obligations we have to fish” (2018, 67). Understanding atikamek as a gift is a form of Indigenous legal order, in which the whitefish is a friend and relative whose many gifts are cherished. As we work with atikamek’s plentiful gifts, we are reminded to respect and protect the waterways that the whitefish call home as reciprocity for their sacrifice. Blight’s artistic projects often draw attention to these legal orders, issuing Anishinaabemowin challenges to the viewer encouraging them to recognize the waterways obstructed by urban development and honour our non-human relations (2018, 2021). A queer Indigenous politic of care extends to our relationships to fish, other non-human kin, the water and ice.

Embodied Queerness

In Woelfle-Erskine’s Fishy Pleasures (2019), fishing is interrogated through a series of images where settler colonialism, settler sexuality, and masculinity are reinforced. In one,

The men hold the heavy fish stick possessively, the women merely gesture to it, acknowledging their mates’ masculine drive. The women stand closer to the men than to each other, one hand holding fishing poles flung over their shoulders and their other hand resting on the trout stick (336).

Fishing for gifts from the fish is an embodied practice of queerness wherein the fishers and practitioners are queer themselves. I fish with my queer Two-Spirit Anishinaabe partner Melody McKiver. We meet the fish and the water, mutually reinforcing our care for each other and the Land. We subvert the heteropatriarchal images surrounding mainstream fishing cultures: two queer and Two-Spirit lovers chopping open the ice, deploying the ice jig, and setting the net. We understand our practice as future-oriented: through learning to fish as Two-Spirit people, we set ourselves up to better prepare for life in a closer relationship with the Land—especially as we face an ongoing climate disaster knowing that neither heterosexuality nor not knowing how to fish will save us. Queerness and gifts from the fish will be what helps sustain us.

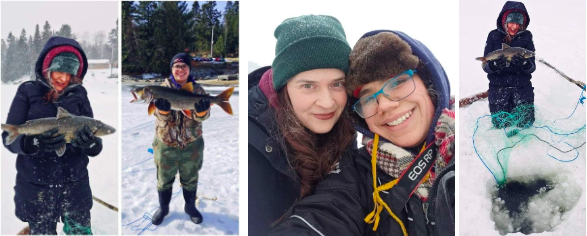

Subversion needs humour too. In Fig. 2, Melody embodies the phenomena of cisgendered heterosexual men proudly displaying their fish catches in an attempt to display their virility, such as in the well-known and oft parodied “Tinder pose”. Speaking back to the “Tinder pose” culture of posing with our fish kin, we orient the gaze of the camera towards our beautiful connection with the fish in Fig 1 and 4, emphasizing reverence for our relations and celebrating queer joy together, Fig 3.

Queer kinship begins with us, but extends to the fish. For many queer, trans, and Two-Spirit people, our families often include more than biological family due to the need to seek out community and kinship that reflects queer experiences. This dynamic is extended through Land to include our more-than-human relations and “fish are chosen family” (personal correspondence, McKiver). In “a world organized around the form of the heterosexual couple” (Ahmed 2006, 19-20), a queer fish scale practice includes reorienting fishing practices as a space for queer people, and valuing gifts from the fish that are often coded as “waste.”

Figures 1-4 left to right: Erin Konsmo (1, 3 left, 4) and Melody McKiver (2, 3 right) fishing together in Sioux Lookout ON, Treaty #3 lands of the Obishikokaang Anishinaabeg.

We humbly add these to the archive of queer photography with fish! Shawna Dempsey and Lori Millan’s infamous “One Gay City!” (1997) was a bus stop poster campaign which sought to portray Winnipeg—heart of the Métis nation and closest major urban centre to where my partner and I frequently fish in northwestern Ontario—as a queer utopia. In one image, a person with short hair poses with a string of whitefish while wearing elaborate beaded gauntlets and a winter jacket. They enthusiastically smile while displaying their fishing prowess, accompanied with the captions “Where the fishing is great!” and “Winnipeg - One Gay City!” The mere act of picturing fishing as an act of queer femininity in 1990s was too radical for mainstream Winnipeg at the time, and the bus stop ads were pulled and only revisited in 2020 (Inglis).

Embodied queerness on the ice and water challenges the many heteropatriachal and heteronormative images that are often conveyed within sport fishing culture. As a queer Indigenous couple we acknowledge that fishing is not a politically neutral site. Métis harvesting rights are both frequently portrayed as fought for and belonging to cisgender, heterosexual Métis men - and First Nations and Métis Land-based practitioners across what is currently known as Canada are all too frequently met with violence and settler colonial resentment (Kerr, 2020) for enacting our relationships with the Land.

On Queer Aesthetics, Fish Glitter

I became a fish scale artist through the process of intergenerational sharing. Like many craft forms, fish scale art is practiced primarily by women. For myself, fish scale art became a space for queering craft, whether that was through manipulation of the original form by utilising digital media, challenging gender norms on the water and even playing with colour. The concept of glitter became a compelling connection between my craft and fish scales.

Glitter is often associated with queerness and is seen in makeup, in drag shows, at Pride events around the world, and in many of the spaces queer people gather in celebration and defiance. In this context, the decorative and glitter-like nature of fish scales is especially compelling. Whitefish scales are iridescent, even before processing—their metallic shine takes on sequin-like qualities. Anyone who has descaled a whitefish knows, you and everything around you are sure to be decorated with this glitter. Descaling a whitefish regales you, resulting in shiny scales in your hair, on your clothing, the table and the ground around you. The fish transforms you with their glitter, showering the processor with irridescent queerness.

The Land and Water are gender-affirming in that they orient us towards worlds where queerness is safe on the water with the fish, our homelands and artistic practices. Here the glitter comes from the water. In this way, glitter is a part of the large kinscape of the Land and Water.

Creative producer and lecturer in art history and visual culture Daniel Fountain speaks about glitter being found in waste and how “things which do not look precious, can turn out to be so” (12). Returning to the initial discussion of fish scales as discardable, the beauty found in this material is a queer craft supply, challenging what is otherwise disregarded.

Digital Media and Augmented Reality

Queer relations exist on Land and Water, regardless of whether that space is rural, remote, or urban. Many queer, trans and Two-Spirit people find themselves in the city for a range of reasons, ranging from access to safety, community, gender-affirming services, or employment. Even within urban spaces we can still find ourselves in relation to fish and the water. Digital media and augmented reality have helped to continue this relationship with whitefish, the act of fishing and the gifts from the fish. Macro-photographs of individual whitefish scales and cones are replicable even when scales are not accessible, allowing for the ability to create fish scale florals without physical scales. The below fish scale floral was created using a single scale and cone to recreate the classic fish scale floral commonly done with physical scales. The creation of this digital fish scale form was created during the beginning months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when isolation was common, including the ways in which our relationship to land, water and fish was ruptured.

Digital fish scale floral, 2021.

Erin Konsmo

An ice jigger is used by fishers in the winter to set a long gill net under the ice between two holes. The jigger is often painted orange to help spot it as it moves under the ice. Gill net fishing is restricted in Canada, but is protected under First Nations and Métis harvesting rights. Atikamek prefers cold water, and ice fishing is an ideal time to greet our whitefish friends. Using augmented reality, a 3D ice jigger can be launched on the concrete streets of a city when water is not close in range. Below is an orange ice jigger and replica of a hole in the ice, ready to be launched on a side street.

Deploying a fish jigger in the city, 2022.

Augmented reality, Erin Konsmo

After moving back to the city, we found atikamek at Superstore, part of the Weston family’s empire, wrapped whole in a plastic bag and distributed by Freshwater Fish, a corporation that buys predominantly from Indigenous fishers in northern Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and the Northwest Territories. The whitefish is sold whole with their guts removed, but have their scales, skin, heads, and vertebrae intact. These store-bought fish remain our relatives, and I think it’s queering to find our relations in the cities and equally value their presence in our urban lives. Both of us are surviving and finding ourselves in these urban spaces. The same care for fish caught out of the city is given for these relations purchased at stores in the city.

The use of digital media and augmented reality allow for the continuation of a fish harvesting practice in the city when fishing (even in urban bodies of water) is not possible.

Conclusion

The iridescence of fish scales illuminate the vibrance of this small gift from the fish, while whitefish call on us to recognize all of their gifts. My fish scale practice is an opportunity to engage the ways that we view these gifts, by magnifying their size, queering relations and finding ways to maintain connection in digital and augmented reality spaces. While a shadow box filled with fish scale florals may be the final product of fish scale art, the process and relationships leading up to this practice are also illuminating. In queering fish scale art through my artistic practice I challenge the gendered binary of the fisherman and the craftswoman.

Works cited

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology : Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006.

Blight, Susan. Guided by Streams. 2018. https://www.susanblight.com/guided-by-streams

Blight, Susan. The Sturgeon Must Live as a Sturgeon: Memory, Traces and Keeping the World Going. 2020. https://www.susanblight.com/_files/ugd/1b68a2_35aa7ef8a31643c0b2216ac26255be80.pdf.

Blight, Susan. 6 Kilometres and 8000 Years Long. 2021. https://artmuseum.utoronto.ca/virtual-spotlight/6-kilometres-and-8000-years-long/

Dannenman, Kaaren. 2019. Personal communication.

Dempsey, Shawna & Lorri Millan, One Gay City, 1997/2020.

Fountain, Daniel. 2021. “All That Glitters Is Gold: Queering Waste Through Campy Craft”. Loughborough University. https://doi.org/10.26174/thesis.lboro.16587026.v1.

Jackson, Z. J., Quist, M.C., & Larscheid. “Growth standards for nine North American fish species”. Fisheries Management and Ecology, vol. 15, no. 2, 2008, pp. 107-118. Wiley Online Library, 10.1111/j.1365-2400.2007.00591.x

Inglis, Lindsay. 2020. “Over 20 Years Later, a Queer Art Project in Winnipeg Reclaims Its Space”. Canadian Art. Accessed May 23, 2022. https://canadianart.ca/news/over-20-years-later-a-queer-art-project-in-winnipeg-reclaims-its-space/

Kerr, Conor. Metis Harvesting in Alberta: Violence, Racism & Resistance. Yellowhead Institute, 2020. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/2020/04/14/metis-harvesting-in-alberta-violence-racism-and-resistance/

Liboiron, Max. Pollution is Colonialism. Duke University Press, 2021.

McKiver, Melody. 2022. Personal communication.

Styres, S. D., and D. M. Zinga. “The Community-First Land-Centred Theoretical Framework: Bringing a ‘Good Mind’ to Indigenous Education Research?”. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne De l’éducation, vol. 36, no. 2, July 2013, pp. 284-13, https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/1315.

Todd, Zoe. “Refracting the State Through Human-Fish Relations: Fishing, Indigenous Legal Orders and Colonialism in North/Western Canada.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 7, 2018, pp. 60-75, https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/30393/23034.

Woelfle-Erskine, Cleo. “Fishy Pleasures: Unsettling Fish Hatching and Fish Catching on Pacific Frontiers.” Imaginations, vol. 10, no. 1, 2019, pp. 325–352. EBSCOhost, doi:10.17742/IMAGE.CR.10.1.11.

Erin Konsmo (they/them/she/her) is a Prairie queer of Métis and settler Canadian descent. They grew up in central Alberta and are a member of the Métis Nation of Alberta. Erin’s arts practice currently focuses on fish scale art; a discipline that they were mentored into by Métis artist Jaime Morse. Using macro photography and digital art, Erin seeks to magnify the gifts from the fish by taking small-in-scale gifts and digitally scaling them up in size.They enjoy spending time ice fishing, processing the gifts from the fish and sharing the glamour and iridescence of fish scales. In spring and summer, Erin enjoys listening to frog songs, picking medicines, and canoeing to visit beavers. Erin is also a textile artist, taking inspiration from her mothers sewing room and loves a good perusal through drawers full of fabric, rick rack, trims and lace.