Apologia and Annihilation: The Coloniality of Apology

Walter Lucken IV

Abstract: In this article, I analyze the German state’s recent apology for its acts of genocide in present-day Namibia in the 1900s, particularly in terms of how it responds to resurgent global struggles concerning racism and colonization. Through the lens of what Nelson Maldonado-Torres has termed the “forgetfulness of coloniality”, I argue that core states like Germany, in performing apologies for their supposed past transgressions, in fact reify racial-colonial regimes of power in terms of how they take as their premise the notion that said transgressions are located in the past and have no continuity with present day political relations. Utilizing the resources of rhetorical theory to make sense of how the genre of apologia functions in this case to stymy and redirect the energies of contemporary radical movements and reify the “abyssal line.” In conclusion, I suggest that decolonization and/or abolition are the only path forward in observation of the impossibility of redress within hegemonic Western legal frameworks.

Keywords: coloniality of power, genocide, German Studies, Southern Africa, rhetoric

“Self-defense in response to accusation is an ontological human trait, as relevant today as it was in the classical period.”-

Sharon Downey, “The Evolution of the Rhetorical Genre of Apologia”.

“Germany must come to the Nama people, and to the Herero people, and to ask for forgiveness…it is up to us to decide if that apology is genuine or not.”

Sima Luipert, Namaqua activist, on the German state’s official apology for its genocide in then South West Africa.

The Oxford English dictionary defines a “refraction” as the “the fact or phenomenon of light, radio waves, etc. being deflected in passing obliquely through the interface between one medium and another or through a medium of varying density” (OED). Generalizing from these examples of light and radio waves switching from one medium to the other, we can see how in refraction something is lost from one perspective but gained from another. Before the COVID-19 pandemic took hold, I was teaching developmental writing as part of the learning community operated by an ethnic studies department (vague for anonymity) when a student raised the idea that gun violence in the United States could never end under current conditions because guns were used in the creation of the United States, particularly against the Indigenous peoples of Abya Yala/Turtle Island.

I have often used this anecdote as an example of how designations like “remedial” or “developmental” are much more racist and harmful than they are accurate or descriptive, noting that the students I teach (mostly Latina/o/x but also Black, Indigenous, and all of the above) display a deep understanding of complex issues. Something is lost, however, in the refraction from that pedagogical encounter and my relationship with my students and how I represent it even within the format available to me in this study. The student’s observation loses something and takes a different shape when refracted through these pages, inescapably becoming tied to my own scholarly ethos and knowledge production. Proceeding from this observation, I imagine how Indigenous ways of knowing and being change shape when refracted through English, Spanish, French or other colonial languages, alongside how the 500 year campaign of violence perpetrated across the globe by European imperial powers refracts through the discourse and systems of symbolic representation circulating through the societies organized around those languages, at least one of which I bear some responsibility for in my capacity as a teacher of the English language. For the purposes of this study, I chose to consider how the German state’s official 2021 apology for its genocidal actions in what is now called Namibia refracts the violence of those actions themselves, and how by studying this phenomenon we can observe how its lessons refract across the globe to my own context somewhere near the fabricated by very real United States-Canada border. This study is the fruit of that effort.

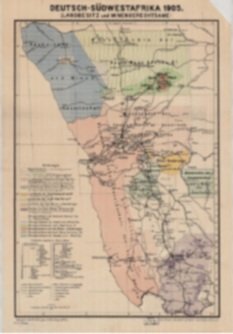

On Friday, May 28, 2021, the German state officially apologized for then Imperial Germany’s perpetration of genocide against the Herero and Nama people in present day Namibia in the early 20th century. Referring to the genocide as such for the first time in an official capacity (after refusing for decades to do so), Germany additionally agreed to fund development projects in Namibia worth billions of Euros, a move welcomed by Namibia’s president Hage Geingob. While the Namibian state was pleased with the official apology, however, other commentators found it wanting or even worse, an insult.

The late Vekuii Rekoro, the paramount chief of the Ovaherero people, lambasted the apology as an “insult” citing specifically Germany’s failure to provide direct financial reparations and the ways in which the Herero and Nama people themselves were excluded from discussions about reconciliation and reparation between the German and Namibian states. Nama commentator Sima Luipert, a descendant of survivors of the genocide, was explicit, noting that the Namibian state, which did not exist at the time of the genocide and had no mandate to speak or make agreements with the German state on behalf of the Herero and Nama peoples. An online post by Luipert and Herero activist Israel Kaunatjike went beyond the symbolic aspects of the apology negotiations to call attention to the state of political relations in present day Namibia, stating that the Herero and Nama peoples did not receive any restitution at the end of the genocide and live in poverty and political marginalization today, in a deeply unequal society where 70% of arable land remains under the control of a small minority of white settlers.

At this moment, I wish to call attention to two aspects of this controversy before moving on to clarify the particular stakes and objectives of the present study. First, it is important to note that Germany’s recent (and of course overdue) recognition of its campaign of genocide against the Herero and Nama people finds its counterparts and contemporaries among a series of apologies by global core societies for the crimes of their colonial pasts, including the Canadian state’s recognition of the atrocities committed in its Indian residential school system, the United States’ somewhat recent official apology for slavery and Jim Crow legislation, the Australian government’s apology for the “Stolen Generations” of Indigenous children removed from their communities, and Belgium’s recent apology for its actions in the present day Democratic Republic of Congo. Thus, while Germany’s recent apology and commitment to aid in Namibia certainly has its own internal causes within German society (including a recent uptick in discussions about racism in Germany), it takes place amid a larger moment of major Western nations publicly and explicitly denouncing their past actions.

Second, all the above-mentioned official state apologies have been controversial domestically, especially finding themselves the objects of critique and refusals to recognize them by members of the groups impacted by their past choices. In these critiques, two common threads emerge: the observation that no amount of financial renumeration or symbolic peans could possibly measure up to the immense destruction and suffering wrought by the actions of the states in question, and the attending observation that the groups impacted continue to be impacted by these events in the present in various guises, most notably in terms of how they continue to experience racism and inequality. In my own local example, the United States, countless commentators have observed that any official apology for slavery or Jim Crow legislation rings hollow when anti-Black racism persists at every level of society, from health disparities to household wealth. In Canada and Australia, Indigenous peoples and communities continue to face extreme racism and social marginalization, owing no doubt in large part to past campaigns of genocide and internal war waged by those states against them.

The purpose of this study, then, is to explore the larger social-historical and rhetorical purposes of these official apologies by powerful Western states, alongside the impossibility of reconciliation and repair within the frameworks that enable the apologies themselves. This is to say, following the observations of Dylan Rodriguez, Joao Costa Vargas, and others that the various atrocities for which these states have both gradually and recently apologized for, rather than being accidents of the past or isolated incidents, are in fact what Olufemi O Taiwo has termed “world making”, meaning that historical formations like racial slavery, the attempted annihilation of Indigenous life in Australia, and Germany’s genocidal actions in southern Africa, are in fact the condition of possibility for the juridical and political frameworks within which the apologies are imaginable. There is, in short, no modern German state to apologize for its campaign of genocide in Africa without the genocide itself. In fact, the German state previously argued that genocide as a juridical concept referring to actions by states did not exist in the early 1900s, and that as a consequence Germany could not be legally culpable for its past actions in that, technically speaking, the attempted annihilation of the Ovaherero and Nama peoples was not illegal at that time. Rachel J. Anderson has repudiated this claim on the grounds that several 19th century treaties of which imperial Germany was a signatory did in fact prohibit some forms of what is now termed genocide in international law (Anderson).

Nevertheless, I take here as my point of departure the premise that what may appear as a contradiction or an error on the part of states like Germany in terms of their official apologies and the ways in which they fall short in fact signifies a “coloniality of forgetfulness”, as Nelson Maldonado-Torres puts it. Noting how modern states have been historically reticent both to officially apologize for their past actions, as well as to acknowledge them as genocides, I place genocide and apology in relation with one another as key genres of rhetorical activity in public discourse, drawing out how official apologies in fact reinforce and reify the coloniality of power underpinning the juridical-legal and social-historical frameworks in which they take place.

Genocide and Annihilation

Genocide as a term and legal concept is a relatively recent invention, having been coined by Polish-Jewish jurist Raphael Lemkin in 1943 for Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, his study of the policies of Axis powers during that period. Moses cites Lemkin as explicitly concerned with Germany’s actions in Africa, noting that Lemkin “was disturbed by” the campaign in terms of how the Ovaherero and Nama people “were assaulted in a concerted attack rather than fading away” (Moses, 28). This particular definition, in turn, became the core of Lemkin’s definition of genocide, which the United Nations adopted in 1948: “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such” (United Nations).

In recent decades, Moses and other commentators have noted the limitations of Lemkin’s concept of genocide, and how it places such stringent conditions on a definition of genocide whose occurrence is very difficult to prove. A critique of the concept much more important for our present study, however, is the extent to which the prevailing definition of genocide focuses on particular actions and official campaigns by states at particular points in time, which in order to prove culpability must have a clearly defined beginning and end. Thus, for a crime against humanity to have occurred, there must necessarily be a period before such a crime began, and a time at which it ended. In the case of many of the more recent ethnic cleansing campaigns in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Darfur, evidence along these lines has been produced, including communiques pointing to intentional campaigns by states and other organizations to destroy in whole or in part particular nations or ethnic groups.

In the case of longer and more protracted cases, however, the concept has been observed to have limited valence, particularly owing to the legal continuity between the states which committed them and the states of the present. What I mean by this specifically is that while innumerable policies pursued by the United States, Canada, and Australia do indeed meet the criteria set forward by the United Nations Convention on Genocide, it is difficult to separate from the overall constitutional frameworks of these states, as well as to mark their beginning an end in a clear way. For an example, the Australian government pursued a number of different strategies to eliminate Indigenous peoples and especially Indigenous culture from Australia over centuries, and some aspects of this process were illegal under present definitions whilst others were not. In the case of Germany, which has cycled through a number of different constitutions and state forms from the Weimar Republic to Nazism and then its own partition and later reunification, it is comparatively less difficult to argue for a legal discontinuity between the perpetrators of the genocide in Namibia and the present day German state (termed such here as it inarguably meets the United Nations definition).

For Dylan Rodriguez and others, the difficulty in establishing a claim of genocide owing to seemingly genocidal actions existing in a state of legal continuity with other, more sanctioned strategies of governance, is not an accident. Rodriguez is explicit on this point, arguing that genocide as a category is an “incomplete accounting of gendered racial and racial-colonial violence” (19). In the opening passage of “Inhabiting the Impasse”, Rodriguez claims that “the capacity to eliminate populations, geographies, ecologies, and ways of life remains the epochal potential at the heart of global racial modernity and its long historical present” (19). This is to say that, paradoxically, the acts and strategies of governance to which the juridical definition of genocide refers are in fact the condition of possibility for modernity itself, particular in the case of powerful states including the United States, Canada, and Germany.

In the example of North America, it has become inarguable that the United States and Canada take the annihilation of Indigenous communities and ways of life as well as racial slavery as their own conditions of possibility, with the current scholarly debate hinging primarily on how to observe this past in terms of resolving and reconciling the issues of the present. While histories of colonization are sometimes occluded in terms of their role in the creation of continental Europe’s core states, especially in the case of Germany and the Netherlands, a similar conversation has attained more public status in those contexts as well. In this way, Germany’s recent apologies, offers of financial renumeration, and the return of the physical remains of Ovaherero and Namaqua elders to Namibia take place within a larger pattern of reconciling with that nation’s colonial past, in response to new developments in domestic and international politics, as well as waves of protest in increasingly diverse European cities and institutions. Extending Rodriguez’s argument, we may note that the German Empire’s capacity to commit acts such as the attempted annihilation of the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples in the 1900s is indeed the primary attribute which distinguishes it as a modern state, a category it shares with the United States, Canada, Australia, and South Africa. Carrying this argument out, we might observe the paradoxical conclusion that the member states of the 1948 United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide were and are themselves states primarily distinguished by their capacity to commit acts comparable to or fully constituting genocide itself. Thus, the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, rather than acting as a prohibition on the annihilation of “populations, geographies, ecologies, and ways of life”, is more accurately noted as an enterprise in determining where, when, and how such acts of annihilation are to be authorized and tolerated by the international community (just page number here).

Another way of thinking about the chiasmic relationship between modern politics and these acts of annihilation, which simultaneously take place in the past and continue to shape the present, is the coloniality of power. While the concept was initially developed within the context of Latin American Subaltern Studies, it has been increasingly taken up as an analytic both in the global South and core nations to make sense of the relationship between past colonization and the global balance of power in the present, including the context of present-day Africa. Put simple, the coloniality of power is the notion that the heterogenous, combined and uneven process of colonization has shaped the modern world at both the global and local level to such an extent that it has continued beyond the decolonization movements of the 20th century. One of the ways in which this analytic is particularly helpful is the extent to which it can simultaneously make sense of the conditions of oppression across national and continental borders, for example, as a method of connecting struggles against police brutality in Los Angeles to similar conflicts in post-apartheid South Africa. Khatija Bibi Khan’s use of coloniality as an analytic to make sense of Germany’s actions in Africa is especially instructive for our purposes here, as it takes the genocide as being in some way constitutive of modern Germany as well as the modern Namibian state, particularly in terms of how the official discourse around the genocide has structurally excluded the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples by design.

Khan’s intervention on Germany’s genocidal actions is framed in terms of how modern African politics takes as its condition of possibility the forgiving and forgetting of atrocities and acts of annihilation on a mass scale by modern European states, a structure of mass violence which has continued into the present in the guise of acts of annihilation by postcolonial African governments including Rwanda, Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Zimbabwe. This is to say that for Khan, as well as Achille Mbembe and a number of other commentators, the spectacle of mass violence across the postcolonial African continent is better understood in continuity with the violence of colonization itself, rather than the preexisting and natural state of African society which has returned in the wake of the departure of European empires.

Nonetheless, for Khan the fabric of modern politics in Africa is framed by what Nelson Maldonado-Torres has termed the “forgetfulness of coloniality”, wherein “the anxieties in the metropole preoccupy the world and put similar catastrophes of third world countries in the penumbra of human agency” (Khan, 212). This is to say that for Khan, following Maldonado-Torres, the same pattern of forgetting and refusing to acknowledge past acts of annihilation takes place both in the relation between states like Germany and their former colonies, but also within the governance of the former colonies themselves, such as the contemporary state of Namibia, in which a small but powerful white elite continues to own much of the land in the country, and the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples continue to face marginalization, dispossession, and poverty. In this sense, both the German and Namibian states exist in a legal continuity relative to the genocide of the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples, despite Namibia’s independence since 1990, previously being a territory of South Africa following a 1920 transfer of administration power.

Khan’s reading of David Olusoga’s The Kaiser’s Holocaust is instructive in terms of how Germany’s juridically indisputable acts of genocide in Africa are difficult to separate from larger patterns of governance and colonial administration which continued to produce similar effects in the region throughout the 20th century, if less visibly or acutely. Noting that Germany’s campaign against the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples began as a military intervention into land conflicts between Indigenous communities and white settlers, Khan goes on to note that “a politic-military organization controlled was a primary agent” of the decline of the Ovaherero and Namaqua people’s populations in the early 20th century (Khan, 214).

Following military campaigns explicitly aimed at the annihilation of the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples was an effort to extend the “coloniality of power” by the creation of “inimical conditions that ensured that the Nama and Herero would die from starvation, dehydration, and exhaustion from overwork”, along with the introduction of disease designed to kill the cattle which sustained both communities (Khan, 215). Thus, beyond active military campaigns in which men, women, and children of both genders were shot and killed, the German colonial administration pursued other tactics to reduce the capacity of the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples’ capacity to reproduce both biologically and socially, applying to these Indigenous communities what Achille Mbembe has termed “necropower”, the state’s capacity to decide who will live or die (Khan, 216). For Khan following Olusoga, this marks the transition into what both authors term the “Silent Holocaust” in Africa, wherein the annihilation of the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples moved from a military campaign to the ongoing maintenance of a political system, the precise moment where the elimination of a region’s Indigenous communities becomes a structure, as opposed to an event (Wolfe). Khan uses this distinction to develop his claim that the scholarly literature on genocide has ignored the conditions of colonization and coloniality, noting that “German colonialism revealed that genocide or holocaust can be achieved not only by shooting or gassing victims, but by creating and enforcing enervating conditions that caused the dwindling of native populations” (Khan, 217).

As I have established previously, such strategies of governance can be difficult to include in a charge of genocide, particularly when the regimes which committed then have some form of legal continuity with the laws which might be used to pursue them today. Particularly when these acts of annihilation were part of the establishment of the modern states of the present (inarguably true in most cases), a paradox emerges wherein the legal and rhetorical frameworks used to “charge genocide” are inextricably bound up with previous acts of annihilation. This paradoxical condition creates conditions of possibility for these states to issue official apologies for their past acts of annihilation which isolate the aspects or instances which have become unacceptable in contemporary political discourse, while eschewing the aspects or instances which continue into the present and are constitutive of contemporary political discourse. This dynamic, moreover, manifests in and through the Canadian state’s various apologies for its past crimes against First Nations peoples in combination with its continued assault on Indigenous life. In this and other examples, then, the purpose of apologizing for past misdeeds is indeed to establish perform the “coloniality of forgetfulness” as it pertains to ongoing colonial (or even genocidal or annihilative) conditions in the present. By establishing the illusion of separation in the face of an actual legal continuity between American slavery and the contemporary carceral state, for example, the United States is able to separate racism from the existing political systems which reify and maintain it, resulting in a paradoxical scenario where the Biden-Harris presidential campaign was able to simultaneously run on a platform of racial reconciliation and unwavering support for police and policing.

At this moment it becomes necessary, then, to draw a distinction between acts of genocide as they exist in historical or legal continuity with the states of the present, in which case they cannot be fully represented within the official discourse of those states, and genocide as a rhetorical genre standing in for the aspects of a nation’s past it wishes to disavow. The naming and repudiation of these acts, then, becomes a rhetorical performance in which a given state’s public officials in fact rehabilitate the state in question, saving face by constructing the contemporary nation-state as won which defines itself in opposition to its own past. This performance, as I have argued above, reinstates what Nelson Maldonado-Torres has termed “the forgetfulness of coloniality” (Maldonado-Torres).

The Coloniality of Apology

We do not need to look far to find scholarship from the history of rhetoric and performance on the changing roles of apology as a genre throughout history. Indeed, as Sharon Downey noted in 1993, the apologia is indeed “the most enduring of rhetorical genres” (Downey, 1993). Downey constructs the apologia as being “precipitated by motives ranging from self-actualization to social repair to survival”, going on to observe that apologia as genre appears most often when a given rhetor responds to “threats against their moral nature or reputation” by “adopting defensive postures of absolution, vindication, explanation, or justification” (Downey, 1993). While I will examine Downey’s reading of the apologia in greater detail below, it is worth pausing for a moment to consider that Downey reads the motivation of rhetors in situations of apology to be entirely self-interested, arguing that the purposes of apology can be related to self-actualization, social repair, or survival on the part of a given rhetor. In the case of Socrates’ apology and similar moments in the history of ancient Greek rhetoric, we might imagine an apologia as a defense of a given individual person in the face of serious accusations and the threat of their own demise, an individual arguing in their own defense so as to survive a given conflict.

When we transition to imagining rhetors as entities other than individual people, or at the very least individual people acting as emissaries of other entities, we see a slightly different picture. In the case of the German state, we recall that an earlier use of the term “genocide” by a German state official was immediately followed by an official statement from that state that they were not authorized to do so, and that their utterance was thus not recognized. Additionally, when we consider the extent to which Downey reads the rhetorical genre of “apologia” to account for a range of different responses by a given rhetor to charges or accusations relating to their moral character or reputation, we can begin to trace a continuity in the strategies pursued by the German state to either defend itself from accusations of genocide by the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples or rehabilitate its own image and reputation by way of an official apology, not to Indigenous groups themselves but to the Namibian state, an entity which continues to marginalize Ovaherero and Namaqua people and communities in its own official discourse.

Tracing the evolution of apologia through the hegemonic Western history of rhetoric, Downey claims that the key factor which changes the rhetorical strategies employed by rhetors across history is the changing constitution of the assumed or perceived audience. In ancient rhetoric, rhetors made their apologetic speeches in an address to the juridical authorities accusing them of a transgression, with the example par excellence of course being Socrates in the Apologia. While the history of rhetoric as written from a mostly 19th century colonial perspective might seem to be of little import to the question at hand, it is indeed worth considering how the implied audience for the German state’s various statements about Germany’s actions in present day Namibia has changed the shape of its apologies, and how changing political conditions might help us make sense of the different statements from different historical periods. In the opening passages of this study, I cited prominent Ovaherero and Namaqua activists as stating unequivocally that the official apology by the German state in 2021 was in fact better interpreted as an insult due to the fact that Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples were not consulted in the decision-making process, in no small part owing to the fact that these groups lack formal representation in the Namibian government. Thus, an official apology from the German state to the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples themselves is impossible within official discourse because these communities lack representation within global political frameworks.

As we have noted previously, this state of affairs is itself a direct result of Germany’s acts of annihilation in the region in the early 20th century, in terms of how Germany’s policy of extermination and confinement of Ovaherero and Namaqua life reverberates into the present, with the marginalization of these communities by the postcolonial Namibian state taking shape as an instantiation of what we have elsewhere cited as “the coloniality of power”. In this sense, Germany’s acts in the 1900s echo through the present rhetorical situation wherein the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples are marginalized and eliminated from the circumstances of the apology itself. The premise that the genocide can be boiled down to the actions of German colonial administrators over a period of several years, as a result, falls flat. Despite the withdrawal of the German state from the region and Namibia’s postcolonial status as an independent state, the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples continue to live under genocidal conditions, conditions which are inextricable from the “normal” everyday functioning of the Namibian nation-state. In this way, the choice of the Namibian nation-state as the audience for the official apology continues to reproduce those same ongoing genocidal conditions while simultaneously relegating them to the “forgetfulness” of the colonial memory. In this way, as Luipert and Kaunatjike state unequivocally, reconciliation is impossible under current conditions, if at all, and the only meaningful way forward is and would be an end to colonial relations of power in present day Namibia. The alternative, as I see it in concurrence with Luipert and Kaunatjike, is a state of affairs wherein the “abyssal line” is endlessly reproduced even as its past instantiations are repudiated and denounced by the world’s continuously and permanently colonial nation-states. How can we draw connections to the context of Abya Yala/Turtle Island, and what sorts of genuine reconciliation or repair are imaginable at all?

Thus far, I have argued that official apologies by powerful states for their previous acts of annihilation reproduce the “coloniality of forgetfulness”, particularly in terms of how they drive a distinction between past transgressions and contemporary political relations. This is to say that I argue that, via apologizing for its actions in Africa, for example, the German state relegates them to the past and obscures how the Ovaherero and Namaqua peoples continue to face conditions of coloniality in present-day Namibia. By apologizing via official channels to the postcolonial Namibian state and not the communities themselves, Germany in effect naturalizes and reproduces colonial relations in Namibia and the broader German-speaking world, as well as crafting an image of itself as a tolerant and multicultural society, the precise sort of society which would condemn such actions as the horrors perpetrated on Ovaherero and Namaqua people and communities in the territory now known as Namibia.

Earlier, I have alluded to how global controversies about racism and colonization in North America and Europe have in many ways placed pressure on continental European countries like Germany and the Netherlands to contend with their racist pasts and presents in new ways, due in no small part to increasing protest movements and antiracist activism within their borders. While I note solidarity between antiracist struggles in the United States and Germany, we should be careful to avoid reproducing the assumption that Black activism and protest in Germany takes its primary inspiration from Black Lives Matter and related movements, which implies that Black life in Germany does not in and of itself present occasions and resources for antiracist activism. Thus, I would not argue that BLM and its antecedents in Europe is the primary causal factor in the German state’s decision to issue an official apology for its past actions in Africa, insufficient as the apology may be, so much as I would note that the direct pressure of protest movements across the Global North and its connections to similar movements in the Global South is both the occasion for Germany’s apologies and those of similar states, as well as the remedy for the impossibility of repair and redress within the legal and political frameworks which generate the apologies.

This is to say that, decolonization and/or abolition is/are the only way forward in the face of these contradictions. Earlier, I noted that the rhetorical genre of apologia in the imagined history of Western rhetoric primarily functions as a self-preservation mechanism for an individual rhetor who finds themselves the subject of accusations of wrongdoing wherein their moral character is called into question. Apologies, in this way of thinking, are primarily self-interested. For states which take acts of annihilation as their own condition of possibility, apologies for these past acts must necessarily take as their objective the continued coherence and ongoing maintenance of their own existence, which itself is coterminous with colonial relations of power.

This is not to say, however, that apology itself must necessarily be dispensed with as a concept. Indeed, an individual person, when confronted with their past actions, must necessarily lose some part of themselves or their self-concept by way of admitting wrongdoing and seeking some reconciliation or redress. There is certainly an inherent vulnerability to apologizing for one’s past choices, and especially in seeking to behave differently, create new sets of relations, or change one’s behavior in the future. That self-same vulnerability, however, is often the only way forward. It is true that the relationship between modernity and acts of annihilation against Black and Indigenous life across the world is inextricable, and that in some sense the harm done is irreparable. This does not mean, however, that different sets of relations are impossible, even if they are impossible to imagine within Western judicial-political discourse. In fact, they are the only possible conditions in which human life on this planet can continue. As Roberto Hernandez puts it in his explanation of the distinction between a decolonial imperative and decolonial option, “we do this or we die”. Decolonization and/or abolition, in every different case, is the only possible course forward, a change in relations and ways of being in common.

Works Cited

Anderson, Rachel. "Redressing Colonial Genocide Under International Law: The Hereros' Cause of Action Against Germany." California Law Review, vol. 93, no. 4, 2005, pp. 1155-1189.

Downey, Sharon D. "The Evolution of the Rhetorical Genre of Apologia." Western Journal of Communication, vol. 57, no. 1, 1993, pp. 42-64.

Khan, Khatija B. "The Kaiser's Holocaust: The Coloniality of German's Forgotten Genocide of the Nama and the Herero of Namibia." African Identities, vol. 10, no. 3, 2012, pp. 211-220.

Luipert, Sima and Israel Kaunajtike. “Renegotiate the genocide agreement WITH US, the surviving Nama & Ovaherero NOW!” Change.org, Accessed April 27, 2022, https://www.change.org/p/abaerbock-renegotiate-the-genocide-agreement-with-us-the-surviving-nama-ovaherero-now

Maldonado-Torres, Nelson. "The Topology of being and the Geopolitics of Knowledge: Modernity, Empire, Coloniality." Revista Crítica De Ciencias Sociais, no. 80, 2008, pp. 71-114.

Moses, A. D. "Raphael Lemkin, Culture, and the Concept of Genocide." The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies. Edited by Donald Bloxham, and A. D. Moses. Oxford University Press, 2010;2012;.

Reuters. “Germany apologizes for colonial-era Genocide in Namibia” Reuters, May 28, 2021 https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/germany-officially-calls-colonial-era-killings-namibia-genocide-2021-05-28/

Rodríguez, Dylan. "Inhabiting the Impasse: Racial/Racial-Colonial Power, Genocide Poetics, and the Logic of Evisceration." Social Text, vol. 33, no. 3, 2015, pp. 19-44.

Smillie, Shaun “German deal an ‘insult’ to Ovaherero and Nama” New Frame, June 15, 2021 https://www.newframe.com/german-deal-an-insult-to-ovaherero-and-nama/

United Nations, Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, United Nations, Accessed April, 27, 2022, https://www.un.org/en/genocideprevention/genocide-convention.shtml

Walter Lucken IV (he/him/his) is a PhD candidate in English at Wayne State University, where he teaches rhetoric and writing with the Center for Latino/a and Latin American studies. His research charts abolitionist horizons in public rhetoric, community writing, and the teaching of writing. In addition to his work at Wayne State, he co-facilitates the Writer's Block creative writing workshop at the Macomb Men's Correctional Facility, serves on the MLA's Committee on the Status of Graduate Students in the Humanities, and is Co-Chair of the Graduate Student Standing Group at this year's Conference on College Composition and Communication. His writing appears in Michigan Quarterly Review, Community Literacy Journal, ROAR, Freedom Arts Journal, Runner, and Refractions Journal. At present, he is starting work on Cavern of Fear: On Rhetorics of Abolition, a book manuscript which explores the potential for abolitionist projects in public rhetoric. He lives in Waawiyatanong (Detroit).