“Dear Nani”

(an Excerpt)

Zinnia Naqvi

Care Work and Worldmaking: An Introduction to Zinnia Naqvi’s “Dear Nani” by Priscilla Jolly

In the following extract from Zinnia Naqvi’s essay titled “Dear Nani,” the artist reflects on inhabiting different linguistic worlds and notions of belonging. Naqvi’s reflections are centered around her grandmother’s photographs, in which her Nani dresses in traditionally male clothing. For Naqvi, these photographs constitute an opportunity to investigate communication, belonging and citizenship in different worlds. The artist begins by noting that the relationship that she had with her grandmother was constrained by language and distance. Theorists from different schools of thought, including Rosi Braidotti and Edouard Glissant have commented on the relationship between languages and identities. In Naqvi’s case, her grandmother’s limited English and the artist’s limited Urdu proved to be challenging. These reflections in the essay gestures to another line of thinking, the theme unifying the current issue of the journal, that of care work involved in worldmaking.

For Naqvi’s Nani, who comes to visit the artist and her mother in Canada, the journey itself is an act of transposing and translating different worlds. While Naqvi, at 5 years old responds to her grandmother’s questions with “ I don’t know,” because of her linguistic limitations, the artist’s return to her grandmother’s photographs reveal a desire to understand the world that her Nani inhabited. Naqvi’s grandmother made the journey from Pakistan to Canada, while Naqvi, in a moment of poetic symmetry, goes on a reverse journey, trying to imagine what would have prompted her Nani to dress as a man and document her experiments. These journeys, both literal and imaginative, showcase acts of care: Nani trying to connect to her grand-daughter by asking her questions and the artist trying to understand her grandmother with a family album. Through these acts of translation that span different worlds, Naqvi’s project demonstrates care work and its involvement in diasporic lives.

—Priscilla Jolly

I wish I could say that I had a more intimate relationship with my Nani, but like many children of immigrants, our ties were strained by distance and language. My mother’s mother was a relatively quiet person. When I was young, Nani would often come from Pakistan to visit my Ammie and Khala in Canada. Because her English was limited and my Urdu was poor, I cannot recall any profound conversations between us. To her questions, I remember responding “Muje nehi patha he,” meaning, ‘I don’t know,’ a phrase I had mastered in Urdu by about age five. She would giggle in response.

Photo historian Martha Langford writes that “an album is an oral-photographic performance.”1 She suggests that the photographic album must be activated by an informed reader or interpreter, one who is able to decipher the clues laid out in the photographs and relay them to an audience. In this instance, the interpreter is my mother, my Ammie, who would look at these images and explain her interpretations to me, a keen listener. The information that I know about these images comes from Ammie’s knowledge of her parents and her understanding of the lives that they had lived.

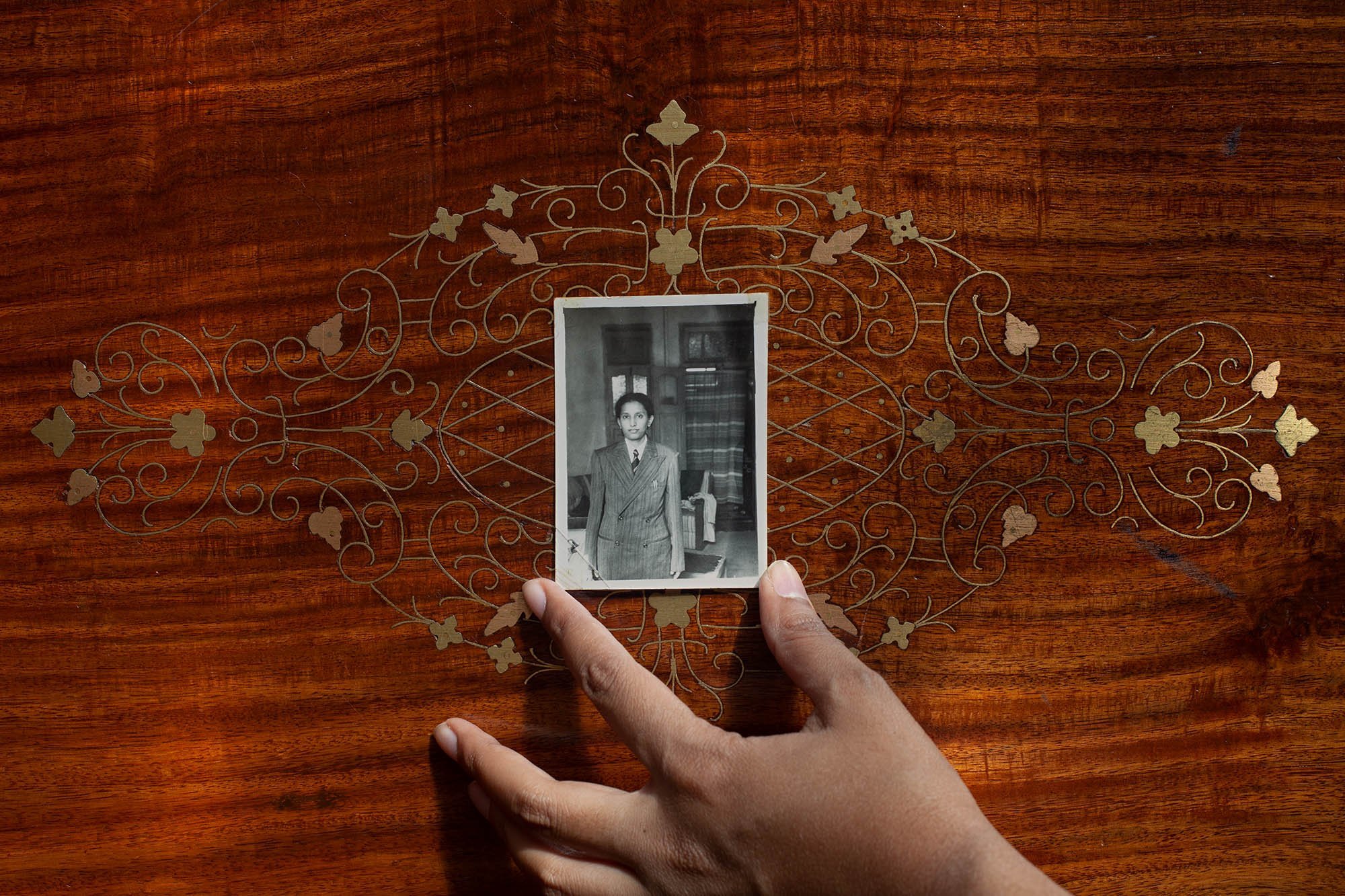

As I went through the album from Khala, I came across the images used in this project - of Nani dressed in men’s clothing. I asked my parents about them immediately. The images were not a secret; Ammie and her siblings knew of their existence but what they knew came from information they had pieced together over the years. The relationship they had with their parents was a formal one and they would not have dared to ask them directly about the photos. It was not a child’s place to ask about the personal photographs of their parents.

As my grandparents are no longer alive, I cannot directly ask why they chose to engage in this act of cross-dressing. What I know about the photos is gathered from my intuition, what I have been told by my Ammie, and my own considerations of the socio-political contexts from when the photos were taken. I have responded to these found photos by creating my own images that attempt to decipher the many clues I read into this performance. I chose to activate this part of the album by adding fiction, re-performance, archival objects, and posthumous dialogue; displaying my position as someone who is outside the performance but embedded in its legacy.

When I came across these images, I already had a history of working with family albums as part of my art practice. The photos I had worked with prior to this were vernacular images that held migration stories of my own family and those of close community members. I examined these images from my lens as an artist, photographer, and archivist; locating political meaning in personal family archives, while questioning ideas of belonging, home, and citizenship.

These images of Nani, however, were so striking on their own that I immediately knew I had to spend time with them. Yet, I struggled to find ways to activate them that maintained their gentle beauty and carried the weight of what they represented. The text which accompanies this

project is an imagined interview I have written, in which I ask Nani about these photos and her memories of them. I was inspired to take this approach after reading “The Politics of Translation,” by Gayatri Spivak, which considers translation a vital tool in archiving feminist legacies. I read this text after attending the workshop “Translation/ Annotation” by feminist working group EMILIA-AMALIA, of which I am now a member. In the workshop, we were encouraged to write about an experience from the position of our mother or a mother figure of our choosing. I have used this strategy in a few of my works. In the case of Dear Nani, it seemed to be the most appropriate way of conveying the oral history that has been shared with me, while also maintaining some of the opacity surrounding these images. In this text component, Nani is giving me the facts, things I have learnt from my mother, but she is also ignoring my questions and refusing to answer me. I choose to pay homage to my family and culture by respecting this distance between generations.

In her text, Spivak laments the need of the third-world subject to translate their writings into English for the sake of the majority, or for gaining access into other feminist spheres. Spivak states, “If you want to make the translated text accessible, try doing it for the woman who wrote it.” One of the most obvious indications that the text I have written is fictional should be that it is written entirely in English. If I wanted to be more authentic about my relationship with my grandmother, it would be written with my questions in English and her responses in Urdu. In reality, this text is closer to a conversation between Ammie and I, as that is how she has relayed what she knows about these photos. The performance of this text is revealed towards the end, when I admit, “I wish I had. I wanted to ask you things, but I was too shy and I didn’t know how.” In this phrase, I regret the loss of knowledge exchange and intimacy that could have been fostered between Nani and I when she was alive - had it not been for the language, distance, culture and time intersecting to make our relationship a distant one. This project is an attempt, on my part, to foster a relationship with my memories of her.

I began this project from a place of intuition and activated it through what I learnt from my mother’s memories and history. The theoretical references that I have included in this long-form text came after the visual component of the project was largely completed. The need for this critical text, and for it to be written from my position as artist, maker, and archivist, comes from a sense of protection I feel in presenting these images to the public. When I first started working with these images, I was worried that they would be read from an Islamophobic and Orientalist lens; that the viewers would see a suppressed Muslim woman acting out against the values of an oppressive state. I knew in my gut that what was occurring here was much more nuanced and that it needed to be disrupted.

From my perspective as a maker working in the West, I see these images as complicating what we expect historical images of South Asian women to look like and depict. From my perspective as a daughter and granddaughter, I see evidence of a young couple at the height of their love for one another. There are socio-political layers beneath this act of performance but alongside them run currents of romance, youth, liberation, and the hidden lives of our elders, which children do not often have the opportunity to witness firsthand. Through these images I can interact with a version of Nani that I did not have access to in my life.

As I write about this work I realize it will never be fully complete; all of the pieces overlap and intersect, yet often lead to new questions rather than answers. Ultimately I will never know precisely what led to this act of gender play and to give agency to the legacy of my grandmother I believe this work must maintain an aspect of opacity. I have fought to keep the gaps alive and maintain that not all aspects of our histories and relationships are meant to be uncovered. I see my role in this project not as an excavationist, but as a maker who lays out the clues at hand, makes interpretations, and keeps space to appreciate what is now gone.

To see more of Naqvi’s work, visit her website.

Works Cited

Langford, Martha. Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001, 20. books.scholarsportal.info/en/ read?id=/ebooks/ebooks0/gibson_crkn/2009- 12-01/1/400191

Chakravorty Spivak, Gayatri. “The Politics of Translation.” The Translation Studies Reader, Routledge, 2021, pp.

Zinnia Naqvi (she/her) is a lens-based artist working in Tkaronto/Toronto, Canada. Her work examines issues of colonialism, cultural translation, social class and citizenship through the use of photography, video, the written word, and archival material. Recent projects have included archival and re-staged images, experimental documentary films, video installations, graphic design, and elaborate still-lives. Her artworks often invite the viewer to consider the position of the artist and the spectator, as well as analyze the complex social dynamics that unfold in front of the camera.

Naqvi’s work has been shown across Canada and internationally. She is a 2022 Fall Flaherty/Colgate Filmmaker in Residence and recipient of the 2019 New Generation Photography Award organized by the National Gallery of Canada. Naqvi is member of EMILIA-AMALIA Working Group, an intergenerational feminist collective. Naqvi received a BFA in Photography Studies from Toronto Metropolitan University and an MFA in Studio Arts from Concordia University. She is currently a sessional lecturer at the University of Toronto and Toronto Metropolitan University.